South Sudan

Nuer Tribe of South Sudan: History, Culture, Religion & Leadership

Nuer Tribe: History, Culture, Religion, and the Future of South Sudan’s Fiercely Independent Nilotic People

Meta Description: A deep historical, cultural, and religious exploration of the Nuer Tribe of South Sudan. Discover their origins, political systems, spiritual beliefs, and modern challenges in this scholarly, in-depth research article.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Ancient Origins and Migration

- Cultural Foundations and Social Structure

- Religion and Spiritual Beliefs

- Political Organization and Leadership

- Nuer-Dinka Relations: Conflict and Coexistence

- Modern History and the Role of the Nuer in Sudanese Politics

- Nuer Diaspora and Global Presence

- Contemporary Challenges

- The Future of the Nuer Tribe

- References

Introduction

The Nuer Tribe is one of the most prominent and historically resilient Nilotic ethnic groups of South Sudan and western Ethiopia. Known for their fiercely independent spirit, complex kinship systems, and deep connection to cattle and spirituality, the Nuer have played a vital role in the social, political, and military history of the Nile Basin.

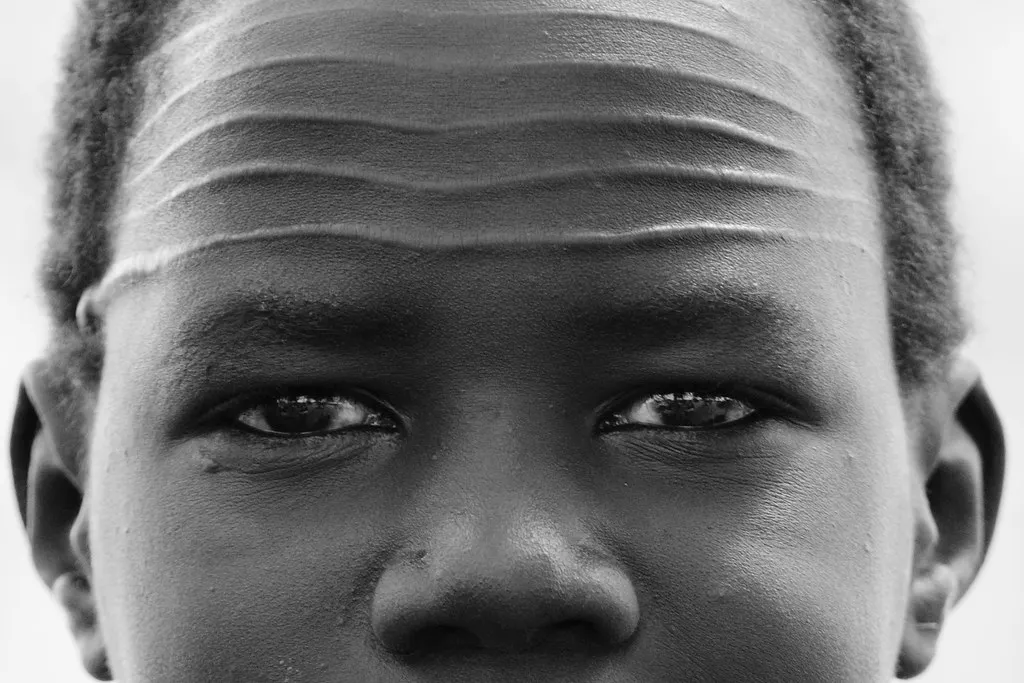

Nuer dancers perform during a cultural celebration, preserving ancestral warrior traditions.

Ancient Origins and Migration

The Nuer are part of the Eastern Nilotic migration that moved from the northeast of present-day South Sudan down toward the Nile Valley around 1000 BCE to 1500 CE. They eventually settled around the Sobat River and the Upper Nile region. Linguistic and anthropological studies confirm their close relation to the Dinka and Shilluk tribes, though the Nuer developed distinct cultural practices over time.

Migration patterns were dictated by seasonal flooding, resource scarcity, and inter-tribal conflict. These movements shaped Nuer adaptability and their deeply ingrained resilience.

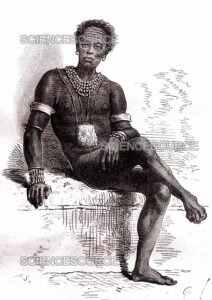

Nuer Chief, 19th Century illustration

Cultural Foundations and Social Structure

The Nuer base their economy and cultural life around cattle. Cattle are not only economic resources but hold immense social, symbolic, and spiritual significance. Each family depends on its herd, and cows are named, exchanged in marriage, and used in rituals. The Nuer social system is based on patrilineal clans and lineages, with exogamous marriage rules and strong age-grade systems.

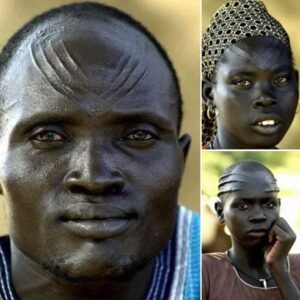

Children are initiated into adulthood through scarification rituals known as gaar, where boys receive horizontal forehead lines, marking courage and social maturity. Girls’ roles are more domestically centered, but they play crucial cultural functions, especially during communal feasts and family rites.

Kinship and Clan Identity

Nuer society is divided into territorial segments called cieng, often centered around a cattle camp. These settlements are semi-nomadic, shifting with seasons. Clans control political alliances, marriage arrangements, and feuding customs, maintaining internal cohesion and external defense.

Religion and Spiritual Beliefs

The Nuer believe in Kwoth, the universal spirit that manifests in various forms. Ancestor worship is a vital element, and spirits are invoked during droughts, illness, or conflict. Cattle sacrifices are performed to appease both Kwoth and ancestral spirits.

The spiritual world is not separate from the physical; rather, it is embedded in daily life through rituals, naming, songs, and taboos. Sacred sites, such as trees, rivers, and ancestral graves, serve as contact points between the living and the divine.

With the arrival of Christian missionaries in the 20th century, many Nuer became Christian while preserving traditional spiritual elements in syncretic forms.

Nuer Tribe Warrior Dance – South Sudan Cultural Festival

Political Organization and Leadership

The Nuer are famously acephalous, meaning they have no central chief or king. Instead, political power is decentralized. Authority is held informally by lineage heads, warriors, and religious prophets known as “gwaan kwoth” or “men of God.” The most famous Nuer prophet, Ngundeng Bong, rose in the 19th century, claiming divine authority and attempting to unify the Nuer against colonial encroachment.

Conflicts were typically resolved through negotiations led by elders and spiritual leaders. Compensation, usually in cattle, played a central role in legal restitution for injuries, murder, or marriage disputes.

Nuer-Dinka Relations: Conflict and Coexistence

Historically, the Nuer and Dinka have shared territories and ecological zones, leading to both cooperation and violent conflict. They have fought over pasturelands, water, and cattle but have also intermarried and traded. Colonial policies of divide-and-rule deepened mistrust, which persisted into modern times.

Inter-ethnic violence flared again during the South Sudanese civil war, particularly in the 2013 conflict that turned political grievances into ethnic massacres.

Modern History and the Role of the Nuer in Sudanese Politics

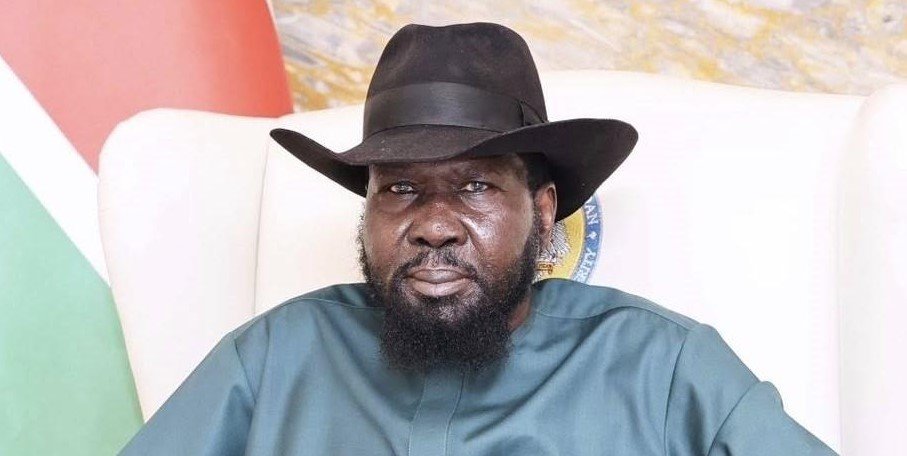

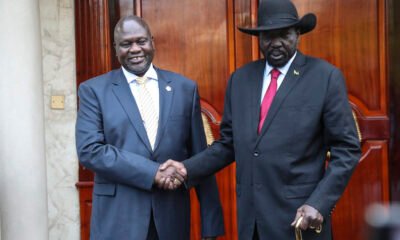

Riek Machar, Nuer political leader and former Vice President of South Sudan

The Nuer have been central to South Sudanese military and political movements. Figures such as Riek Machar played prominent roles in the SPLA/M and the later SPLM-IO (in Opposition). Machar’s 1991 split from the SPLA leadership, allegedly due to ethnic and strategic disputes, intensified the intra-Southern conflicts during the Second Sudanese Civil War.

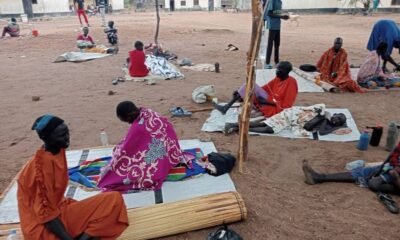

After independence in 2011, hopes for unity collapsed in 2013 when violence erupted between Dinka and Nuer factions. Tens of thousands died in ethnic massacres, and over 2 million were displaced. Nuer civilians were targeted in Juba and elsewhere, leading to ongoing humanitarian crises.

Nuer Diaspora and Global Presence

Refugee crises during the civil wars led to entire generations being educated abroad. Today, vibrant Nuer communities exist in Ethiopia, the United States, Canada, and Australia. These communities have helped preserve language, music, and tradition while building political influence abroad.

In the United States, cities like Omaha, Minneapolis, and Des Moines have seen large Nuer refugee resettlements, where cultural festivals and churches help maintain identity.

Contemporary Challenges

The Nuer continue to face displacement, food insecurity, and identity crises. Climate change has worsened flooding in the Upper Nile region, pushing communities into urban peripheries or refugee camps. Gender inequality, child marriage, and access to education remain critical issues. The militarization of Nuer youth has also raised concerns among peacebuilding organizations.

Despite this, many local leaders and NGOs are actively promoting conflict resolution, inter-ethnic dialogue, and traditional peace ceremonies known as nyuom (reconciliation feasts).

The Future of the Nuer Tribe

The future of the Nuer depends on reconciliation with other ethnic groups, investment in education, climate adaptation, and the nurturing of a new generation of peace-focused leaders. Internal reforms, grassroots reconciliation, and inter-generational knowledge transfer will be key to rebuilding a peaceful and unified society.

The legacy of prophets like Ngundeng and the democratic ideals of Nuer culture offer a strong foundation for progress.

South Sudan

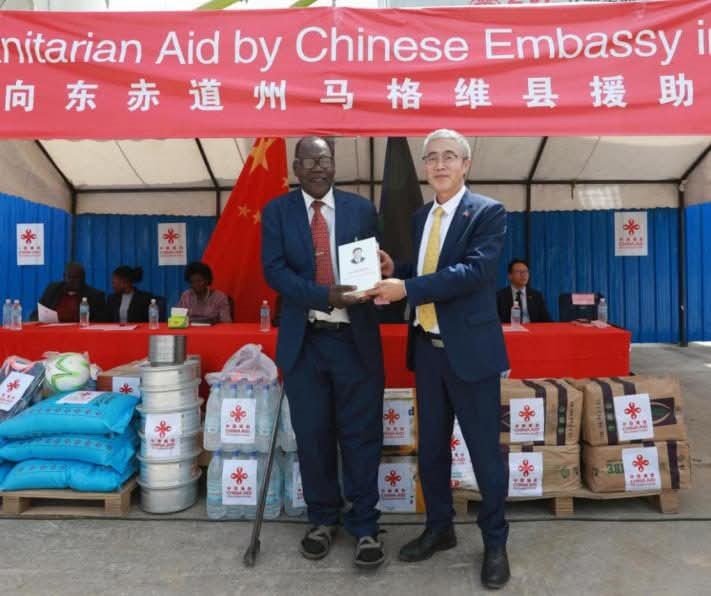

Chinese embassy provides assistance to Magwi

Chinese Embassy in South Sudan Provides Humanitarian Aid to Magwi County

By Staff writer

Key Dignitaries Present at the Ceremony

The Chinese Embassy in South Sudan recently handed over a consignment of humanitarian aid to Magwi County, Eastern Equatoria State. The event, held in Juba, was attended by key dignitaries, including:

- H.E. Ma Qiang, Chinese Ambassador to South Sudan

- Julius Ajeo Moilinga, Chairperson of the Eastern Equatoria State Parliamentary Caucus

- Betty Achan Ogwaro and Lokang Imoya Lujina Salvatore, members of the TNLA

- Mr. Lawrence Akola Sarafino, Director General for Planning, Training and Coordination

Commitment to Humanitarian Assistance

Chinese Ambassador Ma Qiang emphasized that the aid distribution to Magwi County is a result of discussions between Chinese President Xi Jinping and South Sudanese President Salva Kiir Mayardit at the 2024 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Summit. He highlighted China’s commitment to supporting South Sudan’s economic development and improving the livelihoods of its people.

Gratitude from South Sudanese Officials

South Sudanese officials expressed their gratitude for the timely aid, acknowledging the Chinese Embassy’s support in addressing the urgent needs of the population in Magwi County. Moilinga affirmed that the aid would be swiftly distributed to the residents.

Presentation of “Xi Jinping: The Governance of China”

Ambassador Ma Qiang also presented South Sudanese officials with the fourth volume of “Xi Jinping: The Governance of China,” showcasing China’s dedication to building a shared future for humanity.

South Sudan

Kiir appoints new general intelligence chief and security advisor

South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir Makes High-Level Reshuffles

South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir has recently made significant changes to the country’s leadership, including the dismissal of the head of the General Intelligence Bureau (GIB) and the replacement of his presidential security advisor.

New Appointments in Intelligence Leadership

Lieutenant General Simon Yien Makuac, who previously served as the director general of the GIB, was removed from his position without explanation. He was replaced by General Thoi Chany Reat, Kiir’s advisor on national security affairs. The changes were announced by the state-run South Sudan Broadcasting Corporation (SSBC) and took immediate effect.

General Thoi hails from Ayod County in Jonglei State, while his predecessor, General Yien, is from Uror County in the same state. The GIB plays a crucial role in gathering and analyzing intelligence on external security threats, with its director general holding one of the most senior roles in the country’s security hierarchy.

Frequent Changes in Intelligence Leadership

President Kiir has been making frequent changes to intelligence leadership since last October, a departure from past reshuffles that primarily targeted cabinet ministers and military officials. General Yien, who was not reassigned, previously served as deputy commander for finance and administration in the Tiger Division before his appointment as GIB director general in 2021.

Additional Reshuffles in Presidential Security

In a separate decree, Kiir appointed General Madut Dut Yel as his new presidential advisor on national security, replacing General Thoi after just three months in the role. General Madut, a veteran intelligence officer from Northern Bahr el Ghazal State, has a background in Military Intelligence and previously served as South Sudan’s defense attaché in Egypt.

Further Changes in Leadership Positions

President Kiir also replaced Kawaja Kau Madol as undersecretary of the Ministry of Trade and Industry, appointing Achir John Manyuot to the position without providing a reason. These reshuffles reflect Kiir’s ongoing efforts to restructure and strengthen the leadership within key government agencies.

Conclusion

The recent high-level reshuffles in South Sudan’s leadership, including changes in the General Intelligence Bureau and the presidential security advisor’s office, highlight President Kiir’s commitment to enhancing the country’s security and intelligence capabilities. With new appointments in key positions, the government aims to address existing challenges and promote stability in the region.

South Sudan

Dinka People of South Sudan – History, Culture & Spiritual Heritage

Dinka people of South Sudan form Africa’s largest contiguous pastoral society, straddling the flood-plains of the White Nile with a history that threads into Pharaonic Egypt, British colonial cartography, and the modern Republic’s turbulent birth. Renowned for towering stature, intricate scarification, and a cosmology centred on Nhialic—God of the sky—the Dinka have long balanced cattle wealth, clan honour, and diplomatic song. This cornerstone explainer brings together archaeology, oral epics, missionary archives, and UN field reports to paint the most complete portrait yet. Whether you meet a Dinka herder guiding prized luak cattle through a dawn mist or a diaspora scholar in Juba University halls, their story is one of resilience, adaptation, and cultural brilliance.

Origins & Early Migration

Archaeological tracings. Pot-sherds unearthed at Shambe and Fula Rapids date Nilotic occupation of the Upper Nile to at least the first millennium CE.[1]

Linguistic evidence. Proto-Nilotic terms for sorghum and cattle brand suggest an earlier exodus from the Gezira plain around 1400 CE.[2]

Oral memory. Griots recount Alëër, elders who led families south when “waters covered the burial grounds,” echoing a 15-century Nile flood maximum.[3]

Dialect divergence. By 1700 CE, five clusters—Bör, Rek, Agaar, Twic, Ngok—had emerged, retaining mutual intelligibility today.

Herd boys guide their long-horned cows through early-morning smoke on the Nile floodplain, a daily ritual at the heart of the Dinka people of South Sudan cattle culture.

Clan & Sectional Divisions

Dinka society rests on lineage federations called panhom; each clan venerates a bovine-totem ancestor (mien).

- Rek – Aweil heartland; home of 19-century leader Deng Mou.

- Agaar – Rumbek basin; noted for Gok thoom drums.

- Bör – Jonglei floodplain; birthplace of Dr John Garang.

- Twic – Warrap; guardians of sacred spear Thiëŋ Akuei.

- Ngok – Abyei frontier; oil-rich and historically contested.[4]

Alliances renew at annual Gum ë Raan feasts where bulls are sacrificed and disputes arbitrated.

Spiritual Cosmology: Nhialic, Dengdit & Ancestors

Nhialic—“He of the sky”—creates cattle and rain. Subordinate spirits include Dengdit (rain) and Garang (warriors). Failures in rainfall prompt ash-smeared rituals by beny bath priests.

Christianity, introduced in 1905, syncretised: Sunday services often end with the ululation “Wïë Nhialic!”

19th-century engraving of Dinka warriors sharing stories outside bee-hive huts along the Bahr el Ghazal floodplain — a rare historic glimpse into daily life of the **Dinka people of South Sudan** before colonial rule.

Traditional Governance & Age-Sets

Chiefs (Beny Bith) wield sacred spears and the power to bless or curse. Male cohorts (Gar) initiated within three-year windows police cattle camps and host wrestling meets doubling as political assemblies.

Blood-wealth compensation (athoi) still settles homicide cases and is enshrined in South Sudan’s 2008 Customary Law Act.[6]

Cattle Culture: Economy, Bride-Wealth & Symbolism

The night-lit cattle camp (wut) is cultural capital. Bride-wealth averages 30–50 head. Each prized ox receives a personal chant, believed to carry half its owner’s soul (athin).

White Nile riverbank cattle camp where the Dinka people of South Sudan water and rest their long-horned oxen during the dry-season migration.

Oral Literature: Songs, Proverbs & Praise Poetry

Praise-singers (liɔɔc) chronicle war victories or romance in improvised wäl deŋ. Proverbs such as “Liëk acï rïyac ŋaak” (“a cow’s stomach knows no tribe”) urge unity. UNESCO listed Dinka chanting as endangered heritage in 2019.[8]

Dress, Body Art & Scarification

Forehead-line scarification once marked clans—three lines for Rek, V-shape for Twic—now rare. Beaded collars and Shilluk-woven cloth adorn weddings. Ash-striping (thiok) camouflages night raids and repels insects.

Forehead scarification patterns—parallel Rek lines, Twic chevrons, and Bör arcs—illustrate clan identity among the Dinka people of South Sudan.

Cuisine & Food-Security Adaptations

Mainstays: sorghum porridge (wal wal), milk and muit—fermented yogurt-blood. Dried bulu catfish bridges dry-season lean months. Post-flood vegetable gardens led by women cut Warrap malnutrition 18 % since 2020.[9]

Turco-Egyptian, Anglo-Egyptian & Mahdist Encounters

The first written mention of the Dinka dates to 1842 in Ottoman diaries; slave raids peaked with the 1860 sack of Deim Zubeir capturing 7 000 Dinka.[10]

British rule (1899-1956) enforced the Closed District Ordinance, while mission schools at Lui and Shambe birthed a literate elite including independence leader William Deng Nhial.[11]

Mahdist incursions (1881-1898) forced the hiding of sacred spear Thiëŋ Akuei, a tale sung to this day.

Anyanya Wars & SPLA/SPLM Struggle

Dinka youths joined Anyanya I (1955-1972) after massacres at Wau and Akobo.[12] Revocation of the Addis Ababa Agreement triggered the SPLA/M revolt led by Bör intellectual Dr John Garang. Iconic battles—Fangak’s 1993 defence and the 1997 capture of Yei—etched Dinka commanders into liberation lore.[14]

Post-Independence Politics & Inter-Communal Conflicts

Independence in 2011 soon devolved into a 2013 civil war. Grass-roots peace tools, such as the 2017 Akuac Deng cattle exchange, still mend rifts. Recent cholera crises in Warrap, covered here, reveal solidarity beyond faction.

Diaspora & Global Influence

Over 800 000 Dinka live abroad. Communities in Kakuma, Omaha and Adelaide sustain culture through church choirs and online poetry. NBA alumnus Luol Deng funds yearly youth tournaments in Juba, blending sport and cattle-camp ethics.

South Sudan Independence Celebration

Education, Health & Gender Dynamics

Female literacy rose from 7 % (2008) to 18 % (2023) via Girls’ Education South Sudan cash-transfers.[17] Maternal mortality remains high (789 / 100 000) due to distance from clinics. Bride-wealth debates see urban couples shift to mixed cash-and-heifer dowries.

21st-Century Challenges & Prospects

Climate volatility widened the Sudd by 14 % since 2000, squeezing grazing lands.[18] Yet innovations—solar boreholes, peace football, and revived communal labour (Wël Thiec)—show adaptive strength.

Elder Marial Chol, beside a smoky herd, mused: “We move when water moves—Nhialic made us that way.”

The chronicle of the Dinka people of South Sudan is a journey across floodplain, history and imagination—guided by the rumble of hooves and the whistle of a herder greeting dawn.

References

- Gifford-Gonzalez, D. “Nilotic Pastoralism in Archaeological Perspective.” African Archaeological Review, 2018.

- Ehret, C. Historical Linguistics and the Nilotic Migrations. UCLA Press, 2001.

- Wirtz, V. “Hydrological Extremes of the 15th-Century Nile.” Journal of African Paleoclimatology, 2020.

- Deng, F.M. The Abyei Question. Brookings Institution, 2014.

- Lienhardt, G. Divinity and Experience. Oxford UP, 1961.

- Government of South Sudan. Customary Law Act, 2008.

- Luo, J. “Bride-Wealth Inflation in Greater Bahr el Ghazal.” UNMISS Policy Brief, 2022.

- UNESCO. “Dinka Oral Heritage Nomination File.” 2019.

- WFP South Sudan. “Flood-Retreat Gardens Impact Report.” 2024.

- Hill, R. Egypt in the Sudan, 1821–1881. Sealy, 1959.

- Santandrea, S. “Early Missionary Records of Dinka.” Sudan Notes & Records, 1937.

- Johnson, D. The Root Causes of Sudan’s Civil Wars. James Currey, 2003.

- Garang, J. The Call for Democracy in Sudan. Kegan Paul, 1987.

- South Sudan Online Desk. “Comprehensive List of SPLA Battles.” 2025.

- UNDP. “Local Peace Mechanisms in the Sudd Region.” 2021.

- UNHCR. “South Sudanese Diaspora Statistics.” 2023.

- GESS. “Annual Impact Report.” 2023.

- World Bank. “South Sudan Climate Risk Profile.” 2022.

Health5 days ago

Health5 days agoWarrap State Cholera Outbreak 2025: Crisis Deepens Amid Rising Death Toll

South Sudan2 weeks ago

South Sudan2 weeks agoWestern Equatoria Launches Peace Initiative for Youth and Women

Sudan2 weeks ago

Sudan2 weeks agoSudan Army Thwarts RSF Drone Attacks

South Sudan2 weeks ago

South Sudan2 weeks agoNo Political Motive in Giada Shootout

Africa2 weeks ago

Africa2 weeks agoMali Officials Shut Down Barrick Gold’s Office Amid Tax Dispute

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoWarrap State Cholera Outbreak: How Urgent Home Care Can Save Lives

South Sudan2 weeks ago

South Sudan2 weeks agoBor Youth Petition for Wildlife Force Relocation Amid Tensions

Africa4 days ago

Africa4 days agoSouth Sudan on the Brink of Civil War: Urgent Call for Peace Amid Rising Tensions

You must be logged in to post a comment Login