South Sudan

SSPDF warns of ‘punitive aerial action’ against boat hijacking

South Sudanese Forces Demand Release of Hijacked Boats

SSPDF Orders Immediate Release of Seized Vessels

The South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) have issued a stern directive calling for the immediate and unconditional release of hijacked boats and barges in the region. The order comes in response to reports of multiple vessel seizures, including those carrying crucial supplies such as fuel belonging to the Greater Pioneer Operating Company (GPOC).

Threat of Punitive Action

According to SSPDF spokesperson Maj. Gen. Lul Ruai Koang, credible intelligence and complaints from various sources have confirmed that fighters from the SPLA-IO and the White Army have commandeered several vessels in Fangak and Leer Counties in Jonglei and Unity states. The hijackers have not only disrupted river transportation but also engaged in illegal activities that amount to piracy.

- Passengers and crew members held hostage

- Ransoms ranging from SSP 10 million to $50,000 demanded

- Cargo offloaded from the vessels

Concerns Over River Security

This directive comes at a time of heightened concerns over river security in South Sudan. Vice President Taban Deng Gai recently revealed that a fuel boat belonging to GPOC has been held hostage for six months, with hijackers demanding a ransom despite previous payments.

In response to these incidents, SSPDF Chief of Defence Forces, Gen. Dr. Paul Majok Nang, has ordered the immediate release of all hijacked vessels. Failure to comply with this directive will result in punitive aerial and riverine actions to secure the waterways and protect essential transportation routes in the country.

The hijacking of boats and barges in South Sudan poses a significant threat to both commercial activities and the safety of passengers and crew members. The SSPDF’s call for the immediate release of seized vessels highlights the urgency of addressing this issue and restoring security to the region’s waterways. It is crucial for all parties involved to cooperate and ensure the safe return of the hijacked boats to their rightful owners.

South Sudan

White Army of South Sudan: Full Historical Analysis

The White Army of South Sudan: A Comprehensive Historical Analysis

From Indigenous Defense to Armed Insurgency (c. 1800s – 2025)

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Ethno-Social Origins

- Colonial Disruption

- First Sudanese Civil War

- Second Sudanese Civil War

Introduction

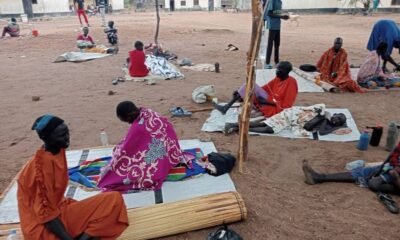

The White Army is a decentralized militia originating from the Nuer youth of South Sudan. Notoriously active during both the Sudanese civil wars and the post-independence crisis of South Sudan, the White Army has been alternately viewed as a tribal resistance force, a tool of ethnic cleansing, and a sociocultural phenomenon. This article explores its evolution through historical, anthropological, and political lenses.

Ethno-Social Origins

Nuer society traditionally groups adolescent males into age-sets responsible for defending cattle and kin. These informal units were known as ‘armies’ and smeared themselves with white ash for symbolic and practical purposes. White ash repelled insects, signified ritual purity, and became a visual marker of unity. These youth ‘armies’ were the precursors of the White Army militia.

Colonial Disruption

Under British rule (1898–1956), indirect administration failed to understand the intricacies of Nuer governance. Attempts to impose disarmament and taxation were met with resistance, cementing a generational ethos of armed defiance. The colonial period also introduced early military tactics, and a mistrust of central authority that persists to this day.

First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972)

Though the White Army was not yet formalized, youth militias supported Anyanya fighters in southern Sudan’s first rebellion. These fighters often operated autonomously, driven by local disputes, access to arms, and spiritual mandates from figures such as Ngundeng Bong, the Nuer prophet who foresaw a divided Sudan and future deliverance through a ‘black messiah.’

Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005)

The White Army rose to prominence during the internal SPLA split in 1991, when Riek Machar’s Nasir faction broke from John Garang. The White Army, mobilized en masse, played a key role in the 1991 Bor Massacre. Amnesty International reported thousands of civilians killed, many by White Army fighters acting on ancestral land claims and revenge narratives. This marked the start of their controversial role in national-level conflicts.

Post-War Demobilization and Reconstitution

The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was a landmark accord that ended decades of war between Sudan’s north and south. However, it failed to address localized militia structures like the White Army. Many fighters, disillusioned with the slow pace of reform and the dominance of Dinka leadership in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), refused to disarm.

Disarmament campaigns—most notably in 2006 in Jonglei State—led to massive resistance. According to the Small Arms Survey, over 1,200 people were killed during these efforts. The White Army saw these operations not as peace-building, but as an attempt to neutralize Nuer power before South Sudan’s independence vote in 2011.

“The UN called it disarmament. We called it invasion. We will not disarm while our enemies are still armed.”

— Nuer White Army commander, 2006 (recorded by IRIN News)

Spiritual Foundations: The Legacy of Ngundeng Bong

Ngundeng Bong, a 19th-century Nuer prophet, remains central to the White Army’s ideological framework. His prophecies are kept alive through oral tradition and written chronicles. According to Ngundeng’s teachings, the Nuer will rise to power after a great betrayal and lead South Sudan into spiritual redemption.

Ngundeng’s pyramid-like shrine in Wec Deang became a pilgrimage site for many White Army fighters, including Riek Machar himself. During the 2013 war, Machar carried Ngundeng’s spear — a move interpreted by many Nuer as the fulfillment of prophecy and a signal to mobilize.

Role in the 2013–2020 Civil War

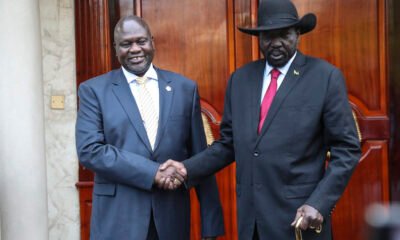

In December 2013, President Salva Kiir (a Dinka) accused his Vice President Riek Machar (a Nuer) of attempting a coup. The fallout unleashed one of the bloodiest ethnic conflicts in modern African history. The White Army, aligning with Machar’s SPLA-In-Opposition (SPLA-IO), launched coordinated attacks in Unity and Jonglei States.

One of the most horrific events occurred in April 2014 during the Bentiu Massacre. Over 400 civilians, many from rival ethnic groups, were killed inside mosques, hospitals, and churches. UNMISS attributed much of the violence to White Army fighters acting under SPLA-IO command, though Machar later denied direct control.

“What happened in Bentiu was not just war—it was ethnic cleansing. Civilians were hunted, not spared.”

— Navi Pillay, UN Human Rights Chief (2014)

Following Bentiu, White Army fighters continued to seize oilfields, loot humanitarian aid, and burn government garrisons. Their guerrilla-style tactics—often uncoordinated but highly mobile—kept government forces stretched across multiple fronts. Some Western analysts, such as Alex de Waal, labeled the White Army as “a mercurial force of destruction and protection, simultaneously destabilizing and vital.”

Tactics, Weapons, and Recruitment

The White Army is not a conventional force. It operates as a loose federation of community defense groups, often numbering in the thousands. Fighters travel on foot or by pickup trucks (known locally as “technicals”) and use AK-47s, RPGs, and stolen military hardware.

- Recruitment: Voluntary, driven by clan loyalty, revenge, and prophecy.

- Leadership: No formal hierarchy, though spiritual elders and commanders hold sway.

- Tactics: Ambushes, cattle raids, village sieges, and riverine assaults.

Many fighters are under 25. UNICEF reported that over 2,500 children were forcibly conscripted into armed groups between 2014 and 2017, with a significant number ending up in White Army units.

International Response and Humanitarian Impact

The global community has struggled to engage with the White Army due to its decentralization. Unlike formal armed groups, it has no spokesperson, no fixed base, and no official channels. The UN has repeatedly condemned its actions but has also acknowledged the socio-economic void that enables its survival.

In areas where the White Army is active, humanitarian operations are nearly impossible. Aid convoys have been ambushed, food warehouses looted, and vaccination campaigns blocked. The 2020 UN OCHA report stated that “over 65% of conflict-driven food insecurity in Jonglei stems from White Army-related activity.”

Post-2020: Revival of the White Army

Even after the signing of the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), the White Army re-emerged in new forms. Peace monitors, including the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (R-JMEC), noted a rise in militia mobilization in Greater Jonglei and Unity States between 2020 and 2023.

In January 2022, White Army militias reportedly massacred over 50 civilians in the town of Pieri. The attack, allegedly in retaliation for earlier Murle cattle raids and child abductions, prompted a condemnation from the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS). The SPLA-IO distanced itself from the attack, suggesting that the White Army had “acted autonomously.”

“We are dealing with a generation that has grown up in war, with no education, no economy, and no government presence. For many, the White Army is not a rebellion—it’s their only identity.”

— David Shearer, former UNMISS Chief, 2022

Intercommunal Violence and Revenge Raids

Many White Army actions after 2020 stem not from national political struggles but localized revenge dynamics. The cycles of violence between Nuer and Murle communities, often triggered by cattle theft and child abduction, have drawn the White Army into brutal reprisal operations.

The use of WhatsApp and Facebook has modernized White Army mobilization. Messages from clan leaders or rumors of an attack can spread in minutes, galvanizing hundreds of armed youth. In 2021, such a campaign resulted in an incursion into Pibor Administrative Area, leading to the deaths of over 150 civilians, according to Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

Women, Children, and the White Army

While the White Army is primarily male-dominated, women have played critical support roles—cooking, treating wounds, hiding weapons, and conducting rituals. In some extreme cases, widows of slain fighters have been known to avenge their husbands by participating in raids themselves.

Children, however, are often the greatest victims. Many are recruited forcibly or born into militia culture. A 2021 Save the Children report found that over 40% of boys aged 10–17 in Leer and Akobo counties had been exposed to direct combat roles.

“My brother was killed. I was given a gun and told to protect the cattle. I was 13.”

— Anonymous former child soldier, interview with UNICEF, 2021

Government Peace Efforts and Ceasefire Struggles

The Government of South Sudan, under President Salva Kiir, has made multiple attempts to neutralize the White Army through disarmament, reintegration, and dialogue. However, these efforts often lack community buy-in or logistical support. The 2021 “Cattle-for-Peace” initiative, which sought to compensate communities with livestock in exchange for surrendering arms, failed due to corruption and inconsistent follow-through.

At the state level, local governors like Gen. Joseph Nguen Monytuil of Unity and Denay Chagor of Jonglei have attempted dialogue with youth leaders. But the absence of a singular White Army command structure continues to hinder negotiations. Efforts are often disrupted by isolated attacks, clan feuds, or broken promises.

Meanwhile, UNMISS and NGOs like the Community Empowerment for Progress Organization (CEPO) have focused on youth outreach, trauma healing, and education as long-term solutions. CEPO’s “Youth Without Guns” campaign, launched in 2022, aims to create economic alternatives for at-risk male youth across Leer, Ayod, and Pibor counties.

The Future of the White Army

The question of what lies ahead for the White Army remains unresolved. As of 2025, the group is still capable of mobilizing thousands, especially in times of perceived Nuer vulnerability or government betrayal. Yet, cracks in its influence are emerging.

Urban migration, increased internet access, and the gradual integration of rural youth into educational programs are shifting mindsets. Former fighters, now in their late 20s or 30s, are returning to farming, joining local security forces, or becoming vocal advocates for peace.

“We cannot eat the gun. The cattle are fewer. The land is tired. It’s time to fight for peace, not for clan.”

— Peter Gatwech, ex-White Army youth leader, Jonglei Peace Forum, 2024

International experts argue that the White Army will only disappear when its economic, cultural, and spiritual foundations are replaced with viable alternatives. These include:

- Increased access to education and vocational training

- Land dispute resolution mechanisms

- Spiritual reconciliation between prophets and political elites

- Community-led disarmament and trauma healing initiatives

However, if disarmament is forced again—without alternative livelihoods—the militia may once again reassemble, perhaps under a different name, but with the same grievances.

The White Army is not simply a militia—it is a product of colonial distortion, state failure, youth marginalization, and spiritual prophecy. It cannot be defeated by military means alone. It must be understood in full, from the dust-covered cattle camps of Nasir to the haunted oilfields of Bentiu, if South Sudan is to ever disarm not just its youth, but its history.

This article has sought to present not just a timeline, but a tapestry—woven of trauma, hope, prophecy, and power. The road ahead for the White Army, and South Sudan itself, will depend on how the world chooses to engage with these deeper truths.

South Sudan

Escalating Conflict Threatens South Sudan’s Peace Agreement Implementation

The escalating conflict in South Sudan poses significant threats to the implementation of the revitalized peace agreement signed on May 2, 2025. Major General Kuol Manyang, senior presidential advisor and chair of the National Transitional Committee, delivered a grave warning during a meeting with the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (R-JMEC).

Verification Teams Facing Increasing Security Risks

Verification teams responsible for inspecting troop assembly and training sites are facing heightened security risks, severely impacting their ability to operate effectively. Manyang highlighted specific concerns regarding regions experiencing intense conflict, such as Nasir, where recent clashes have rendered team movements unsafe without prior clearance from the Defense Committee.

“The current situation does not allow for the safe movement of verification teams,” Manyang stated emphatically. “Deploying teams under these conditions is irresponsible and endangers lives. Urgent security measures must be established before proceeding with the implementation of the peace agreement.”

Manyang noted that an upcoming assessment report classifying risk levels across different regions is vital. This report will determine operational safety measures and guide future deployment strategies for the verification teams.

Delays Impacting the Peace Agreement’s Implementation

Despite ongoing difficulties, R-JMEC affirmed its ongoing commitment to collaborating with the South Sudanese government in implementing Chapter Two of the peace accord, primarily focused on troop unification. However, significant logistical challenges combined with prevailing security concerns have dramatically slowed progress.

The renewed tensions across various regions in South Sudan exacerbate an already precarious peace process. These issues underscore the urgency for immediate and effective security interventions to facilitate the smooth implementation of the peace agreement.

Urgent Action Required to Enhance Security

Addressing these escalating threats requires urgent and decisive security measures. Manyang emphasized that ensuring the safety of verification teams is paramount before any further deployments can be considered.

Rapid implementation of robust security protocols will be crucial for protecting lives, bolstering confidence in the peace process, and mitigating further instability in South Sudan.

Ensuring a Sustainable Path Forward

As South Sudan navigates the complexities of post-conflict reconstruction and reconciliation, it is critical that all stakeholders—including government authorities, peace-monitoring bodies, and international supporters—remain steadfastly committed to the peace process. Transparent coordination and swift responses to security threats will play a pivotal role in achieving a sustainable and lasting peace.

The effective and timely implementation of the peace agreement ultimately depends on collective determination and proactive strategies addressing security challenges. The forthcoming period will be decisive in shaping the future stability and peace of South Sudan.

South Sudan

Gen. Dr. Paul Majok Nang Orders Immediate Release of Seized Boats and Barges in Jonglei and Unity States

Gen. Dr. Paul Majok Nang Orders Release of Seized Boats and Barges

Chief of Defense Forces Gen. Dr. Paul Majok Nang has issued a directive for the immediate and unconditional release of all boats and barges seized by elements of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in-Opposition (SPLA-IO).

Immediate Action Ordered

In a decisive move aimed at restoring order, Gen. Dr. Nang stressed that non-compliance with this directive would result in punitive actions. The order addresses recent illegal activities disrupting river transportation and commerce.

Violations and Disruptions Highlighted

SSPDF Spokesperson Gen. Lul Ruai Koang detailed significant violations by SPLA-IO fighters and the White Army, highlighting incidents of hijacking boats and barges in Jonglei and Unity States.

According to Gen. Koang:

- Boats have been commandeered, with cargo forcibly offloaded.

- Passengers and business owners have been taken hostage.

- Ransom demands ranging from SSP 10 million to USD 50,000 have been reported.

These acts have severely disrupted transportation and commerce, amounting to piracy.

Operational Orders Issued

Gen. Dr. Nang emphasized the immediate and unconditional release of all captured vessels. He warned that failure to comply would trigger punitive aerial and riverine operations.

This directive aims to reinforce security along crucial waterways and restore confidence among travelers and business operators.

Restoration of Order and Safety

The directive from Gen. Dr. Paul Majok Nang underscores the importance of maintaining a secure and reliable river transportation system. Prompt compliance will significantly enhance regional stability and economic activities.

The SSPDF remains vigilant, ready to enforce this directive to ensure the safety and rights of civilians and business stakeholders.

Health7 days ago

Health7 days agoWarrap State Cholera Outbreak 2025: Crisis Deepens Amid Rising Death Toll

Sudan3 weeks ago

Sudan3 weeks agoSudan Army Thwarts RSF Drone Attacks

Africa6 days ago

Africa6 days agoSouth Sudan on the Brink of Civil War: Urgent Call for Peace Amid Rising Tensions

Health6 days ago

Health6 days agoWarrap State Cholera Outbreak: How Urgent Home Care Can Save Lives

Africa3 weeks ago

Africa3 weeks agoMali Officials Shut Down Barrick Gold’s Office Amid Tax Dispute

Africa3 weeks ago

Africa3 weeks agoInvestment App Freezes Users Out, Sparking Savings Loss Fears

Entertainment3 weeks ago

Entertainment3 weeks agoEntertainment Needs Corporate Support

Entertainment3 weeks ago

Entertainment3 weeks agoDynamiq Urges Leaders to Visit Uganda Refugees

You must be logged in to post a comment Login